Mass Spectrometry (MS) is a powerful analytical technique that measures the mass-to-charge ratio (m/z) of ions to identify, quantify, and elucidate the structure of molecules. It provides information about molecular weight, elemental composition, and fragmentation patterns, making it indispensable in chemistry, biochemistry, pharmacology, forensics, environmental science, and clinical diagnostics.

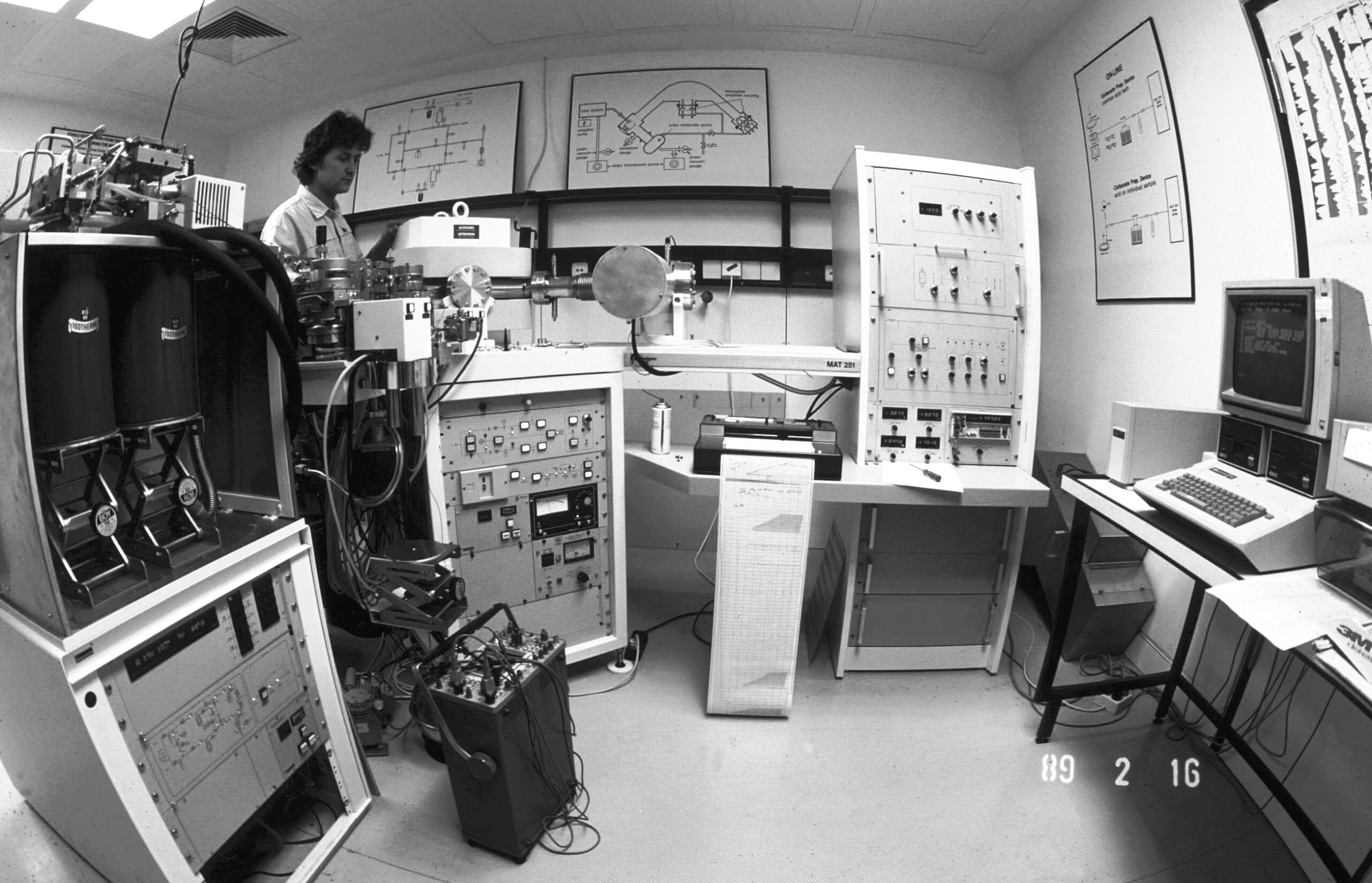

The foundations of MS date to J.J. Thomson’s discovery of the electron and isotopes using a primitive mass spectrograph in 1912. Francis Aston refined the technique in 1919, earning the 1922 Nobel Prize in Chemistry for isotopic measurements. Modern MS exploded in the mid-20th century with organic applications, and today thousands of instruments operate worldwide. The global MS market exceeds USD 7-8 billion annually as of 2025, driven by advancements in proteomics, metabolomics, biopharmaceutical characterization, and high-resolution accurate mass (HRAM) systems.

Principles of Mass Spectrometry

MS involves three core stages:

- Ionization: Conversion of neutral molecules into gas-phase ions.

- Mass Analysis: Separation of ions based on m/z.

- Detection: Measurement of ion abundance.

The resulting mass spectrum plots ion intensity versus m/z, with the molecular ion (M⁺• or [M+H]⁺) indicating molecular weight and fragment ions revealing structure.

Resolution (R = m/Δm) and mass accuracy (ppm error) define performance. Modern HRAM instruments achieve R > 100,000 and <1 ppm accuracy.

Ionization Techniques

Choice of ionization determines analyte suitability:

- Electron Ionization (EI) Classic for volatile organics; 70 eV electrons produce radical cations (M⁺•) and characteristic fragments. Standard for GC-MS libraries.

- Chemical Ionization (CI) Softer; reagent gas (methane, ammonia) produces protonated/deprotonated molecules with minimal fragmentation.

- Electrospray Ionization (ESI) Gold standard for liquids/LC-MS; generates multiply charged ions ([M+nH]ⁿ⁺) ideal for biomolecules (proteins, peptides).

- Atmospheric Pressure Chemical Ionization (APCI) For less polar/small molecules; corona discharge ionization.

- Matrix-Assisted Laser Desorption/Ionization (MALDI) For large biomolecules; laser pulses on matrix-embedded sample produce mostly singly charged ions.

- Others: Fast atom bombardment (FAB), field desorption (FD), atmospheric pressure photoionization (APPI), desorption electrospray ionization (DESI) for surfaces.

Mass Analyzers

Analyzers separate ions by m/z:

- Quadrupole: Fast, robust, moderate resolution; standard in triple-quad (QQQ) for quantitative LC-MS/MS.

- Time-of-Flight (TOF): High speed, unlimited m/z range; excellent for MALDI and HRAM.

- Ion Trap: 3D or linear; MSⁿ capability (sequential fragmentation).

- Orbitrap: Ultra-high resolution (>500,000) and accuracy; dominant in proteomics.

- Fourier Transform Ion Cyclotron Resonance (FT-ICR): Highest resolution (>1,000,000); research-grade.

- Magnetic Sector: Historical; high resolution but bulky.

Hyphenated systems (GC-MS, LC-MS) combine separation with MS detection.

Detectors and Data Acquisition

- Electron multipliers, photomultipliers, or Faraday cups measure ion currents.

- Modern systems use high-dynamic-range detectors for trace analysis (fg-attogram sensitivity).

Data modes:

- Full scan: Broad m/z survey.

- Selected Ion Monitoring (SIM)/Multiple Reaction Monitoring (MRM): High sensitivity quantification.

Applications

MS versatility spans disciplines:

- Proteomics: Peptide sequencing, post-translational modifications (bottom-up/top-down).

- Metabolomics/Lipidomics: Small molecule profiling.

- Pharmaceuticals: Drug discovery, impurity profiling, pharmacokinetics.

- Environmental: Pollutants (PFAS, pesticides), dioxins.

- Forensics: Drugs of abuse, explosives, toxicology.

- Clinical: Newborn screening (tandem MS), therapeutic drug monitoring.

- Food Safety: Contaminants, authenticity.

- Petroleomics: Complex hydrocarbon mixtures.

Imaging MS (MALDI-IMS, DESI) maps spatial distribution in tissues.

Advantages and Limitations

Advantages:

- Unmatched sensitivity/specificity.

- Structural elucidation via fragmentation.

- Wide analyte range (small molecules to intact proteins).

- Quantitative precision.

Limitations:

- Sample must be ionizable/volatilizable.

- Matrix effects in complex samples.

- High instrument cost/maintenance.

- Interpretation requires expertise.

Recent Advances (as of 2025)

- HRAM Orbitraps: Routine sub-ppm accuracy.

- Ion Mobility Spectrometry-MS (IMS-MS): Separates isomers, adds conformational data.

- Miniaturization: Portable MS for field analysis.

- AI/Data Processing: Automated peak picking, compound identification.

- Native MS: Intact protein complexes.

Sample Preparation

Critical for success:

- Extraction (LLE, SPE, QuEChERS).

- Derivatization for GC.

- Enzymatic digestion for proteomics.

Conclusion

Mass spectrometry stands as one of analytical chemistry’s most transformative techniques, evolving from isotopic measurements to routine characterization of complex biologics and trace contaminants. Its combination of sensitivity, specificity, and versatility ensures continued centrality in scientific discovery, quality control, and diagnostics. Ongoing innovations in resolution, speed, and accessibility promise even broader impact across research and industry.

More articles by ZMR Researche:

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/clot-management-devices-market

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/acellular-therapy-market

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/assembly-automation-systems-market

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/sous-vide-machine-market

https://www.zionmarketresearch.com/de/report/aromatic-compounds-market